CIHE board member Sean Conway recommends the two-volume biography of Thomas D’Arcy McGee by CIHE contributor Professor David A. Wilson: “I can think of no better exercise for anyone keen to explore Canada Strong and Canada Proud than to acquaint themself with the remarkable life and times of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, the Irish-born prophet of what he called ‘a new nationality’ for British North America, as pre-Confederation Canada was called 160 years ago.”

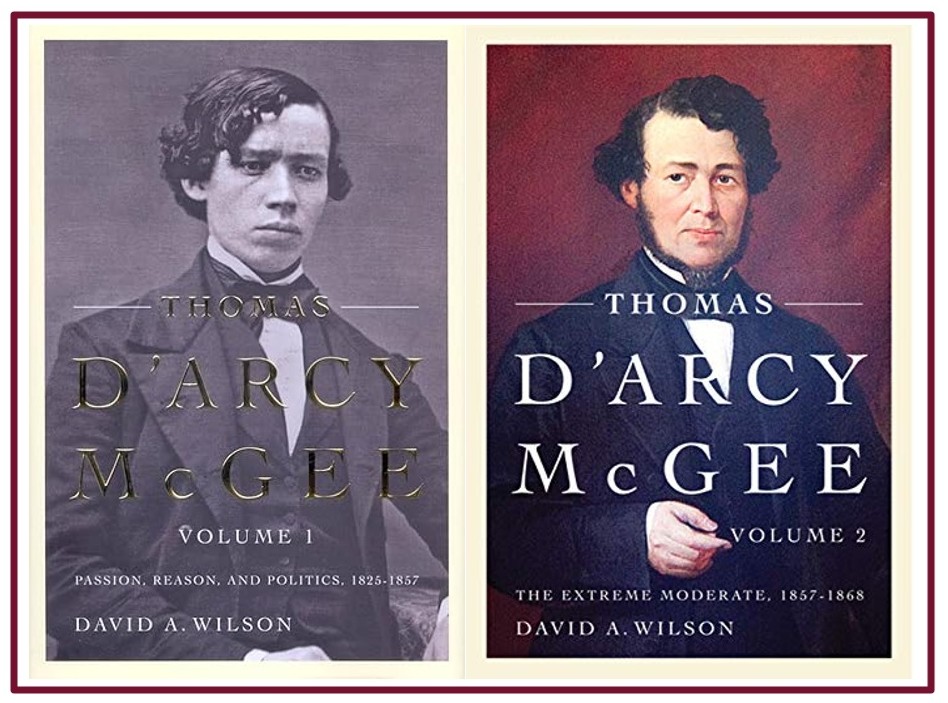

Review of David A. Wilson’s two volume biography, Thomas D’Arcy McGee. Volume 1 Passion, Reason, and Politics, 1825—1857; and Volume 2 The Extreme Moderate, 1857—1868, published by McGill—Queen’s University Press in 2008 and 2013.

By Sean Conway

13 April 2025

April 13th 2025 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth in Carlingford, Ireland of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, the legendary Irish-Canadian journalist, poet and mid-nineteenth century politician. At a time when Canadians everywhere seem determined to discover more about their national identity and the historical forces that lie behind that identity, I can think of no better exercise for all those who are keen to explore Canada Strong and Canada Proud than to acquaint themselves with the remarkable life and times of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, the Irish-born prophet of what he called ‘a new nationality’ for British North America as pre-Confederation Canada was called 160 years ago. And I can think of no better place to start one’s education in this regard than by reading the brilliant two-volume biography authored by the distinguished Canadian historian David A. Wilson and published by McGill—Queen’s University Press in 2008 and 2013.

If Canadians generally know anything about D’Arcy McGee, I would guess they know one of two things. They might remember that somewhere in a high school history class they heard that McGee, like his sometime parliamentary colleague John A. Macdonald, often mixed his politics with large doses of alcohol which usually impaired his health, home life and often his political standing. A second item that might have impressed itself upon the historical consciousness of Canadians of a certain age is that McGee’s life ended suddenly with an assassin’s bullet in the early hours of April 7th, 1868 in Ottawa after a late night sitting of the Canadian House of Commons.

Both of the above stories are true but as Professor Wilson makes plain, there is so much more to the McGee story that anyone reading the two volumes of this biography will be astonished by what McGee accomplished in the 43 years he spent on this earth, only 10 of which had been spent in what we now call Canada. And given the angst and anger these days about what the Trump Administration seems intent upon doing to our sovereignty, our economy and our national pride, the McGee story is also a telling one for before he came to Canada in 1857, McGee had spent the previous ten years in Boston, New York City and Buffalo where he discovered that the Irish, especially Irish Catholics, faced a wall of ethnoreligious and economic discrimination.

Famously, McGee often remarked that the Irish in the America of the 1850s enjoyed a status below that of African-Americans. As the United States hurtled toward civil war, American politics, especially in the big cities of the Northeast, was increasingly anti-immigrant and often anti-Catholic as well. McGee who arrived in America in 1842 and had travelled widely throughout New England and New York state became increasingly disillusioned by what he saw happening to his Irish-Catholic co-religionists in heavily urbanized communities like New York City, Boston and Buffalo. A largely rural people were all of a sudden living in over-crowded tenements and dependent on big city bosses for their welfare. After a while, McGee was appalled by the materialism, the violence and the homogenization of American life. A couple of trips to Canada in 1852 and 1856 set the stage for his accepting an invitation from the Irish community in Montreal to come to that city and promote their interests with a newspaper and perhaps some political representation.

What is so fascinating about McGee is that by the time he settled in Montreal, he had undergone a major reversal in attitude toward the British Empire and the Roman Catholic Church, both of which he had strongly opposed in his earlier life. In both Quebec and Ontario, McGee was impressed by the evident tolerance amongst various religious and linguistic communities, by the existence of state-supported separate schools in much of the country and by the enormous potential for a country as large and as resource-rich as Canada. He also came to appreciate that developing under the Union Jack, Canada had clearly struck a better balance between freedom and order than had their American neighbours. Once established in Montreal, it wasn’t long before MeGee found himself elected to the Union Parliament representing the Irish community of Montreal West.

From his first election in December 1857 until his death a decade later, McGee was part of a fast-moving and a fast-changing political environment. Responsible government or what we would today call democratic government had arrived in the Province of Canada with the Great Reform Ministry of Louis-Hippolyte LaFontaine and Robert Baldwin in 1848, a move to freer imperial trade imposed on the colonies by London, huge migration into places like Ontario and the rapid advance of railroads all combined to change the basis of political organization and those alliances required to provide stability in government. McGee who was far and away the greatest orator of his time quickly endorsed the federal principle as the best instrument by means of which to harness the great potential of this new land. He favoured moderation and compromise in dealing with those issues calculated to divide communities along racial and religious lines and he strongly advocated for the development of a national literature to help create a true national spirit.

The one issue where McGee would give no quarter was the rise of a militant, physical force Fenianism spreading throughout the Anglo-American world of the 1860s. McGee had forsaken his embrace of revolutionary nationalism in the Ireland of his youth in the late 1840s. Now twenty years later, he attacked Fenianism with great vigour and not always with much discretion. Professor Wilson characterizes the McGee of the 1860s as “an extreme moderate” in the turbulent waters of Canadian politics of that pre-Confederation period. A reading of the Wilson thesis strongly suggests that McGee had miscalculated the size of the Fenian Brotherhood especially within the Irish community of Montreal. There were more members of this violent secret society than McGee seems to have appreciated and those Fenians were increasingly infuriated by the vitriolic nature of McGee’s attack upon them, both at home and abroad. As a minister in the Canadian government, McGee travelled to Ireland in the spring of 1865 and in a speech given by him in Wexford, McGee attacked Fenians frontally making no effort to restrain his language. That Wexford speech had its desired effect and afterwards, militant Fenians everywhere in Canada and elsewhere pledged themselves to avenge the apostasy of Thomas D’Arcy McGee, now considered worse than a traitor to Ireland. The day of reckoning for the blasphemy at Wexford came three years later on a mild spring night in early April under a full moon outside Mrs. Trotter’s boarding house on Sparks Street in downtown Ottawa.

The McGee story is an utterly fascinating tale about a time a long time ago when Canadians struggled over many generations to fashion a country out often discordant ingredients and often under the menacing stare of the American eagle. There was no straight-line progression to easy advance or success. One of the cruel ironies of the McGee legacy is that for someone who is remembered by many as “ the golden voice of Canadian Confederation”, there are countless Canadians today who have no idea that this, the youngest Father of Confederation met his end in an act of political violence within the Irish-Canadian community that was so unusual in a country pledged to peace, order and good government and in a country with a history that is generally very respectful of those core values.